trying to teach the people

[note: I’ve been reading the Chinese original]

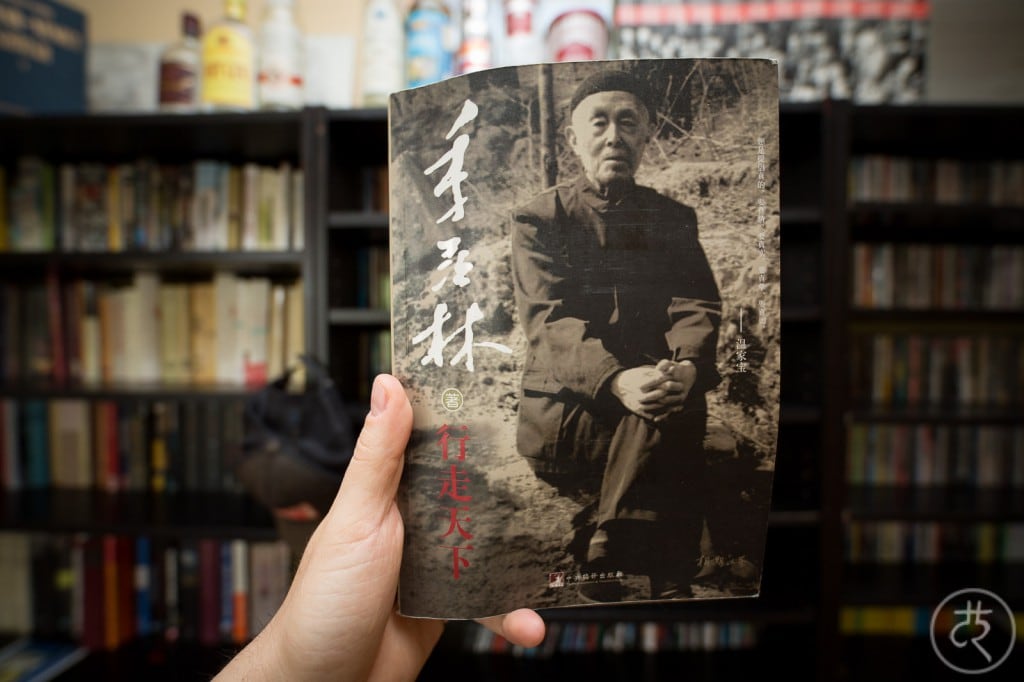

The story: in the early 1930s, Ji Xianlin is a promising student from China who gets the chance to go to Göttingen, Germany, in order to pursue a university degree.

Due to the political situation, though, he has to stay much longer than anticipated, returning home only in 1946 to take up a professorship at the University of Beijing. Ji does research on Indian and Central Asian cultures and gains international fame by the end of the century.

collection of Ji Xianlin’s essays

This book is a collection of essays and stories from his years in Germany, his visits to India, Japan, and Taiwan, and from his life in China. I found his style of writing a bit weird at first: here was an outstanding scientist, an intellectual, who seemed to be continuously talking about his „beloved motherland“, about its „glorious future“ and so on and so on.

an educated philanthropist

But then I started to understand: first of all, Ji Xianlin is writing and publishing in the People’s Republic of China, which could also be called the Party’s Republic of Censorship. There are certain obligations.

Secondly, Ji sees himself as a humanist and a philanthropist whose duty it is to try to improve his society by writing about it – and thus, some of his messages tend to come in a certain packaging.

For example: in an article about his trip to India, he glorifies the friendship between India and China, telling us how the Indians love the Chinese, etc. etc. – only a few years after there was a war between the two countries.

In another essay, he introduces Japan as China’s cultural offspring at first – only to go ahead and point out the many things that the Chinese could actually learn from the Japanese.

In his evaluation of the situation in Shenzhen in the early eighties, he rejoices about the fact that the „iron rice bowls“ have finally been shattered and that efficiency might finally reign – an underhand critique of Mao’s economic policies.

lengthy but charming

As you can see, I enjoyed reading this book, mainly because Ji Xianlin seemed like a charming old man who did not only attach high value to intellectual curiosity, but who also tried to defend his society against some of the more radical political ideas that he saw floating around.

His defence of Hu Shi (胡适), for example, is a particularly charming one: Hu, a fellow scholar, had been opposed to Communism and fled to Taiwan. For this, he had been criticized even beyond his death. To Ji Xianlin, this didn’t make any sense: wasn’t it normal, he wondered, that a bookworm like Hu Shi could not be interested in radical political ideas? What was everyone fretting about?

who might want to read this

There is a feat here: Ji Xianlin managed to stay alive not only as a Chinese student in Nazi Germany, but also as a scholar in Mao’s China. This is quite a remarkable feat actually. His storytelling is good. His style could be better, were it not for a certain wordiness and the repetitions of the “beloved motherland”. His observations and insights are great.

If you’re into China in the 20th century, and you are aware of the implications of censorship on this publication (and on others like it), then by all means read this.

Also read: Ma Jian, for a travel story from a more angry person.